John C. Burnam’s story began in 1967, yet it won’t be complete until 2012. His heroes are not just characters in a book. They are real. They are loyal. And they are man’s best friend.

For many years Burnam has been on a personal journey to honor U.S. Military Working Dog Teams. It has been a long road with many unexpected turns. But the end is now in sight.

Let’s talk about A Soldier’s Best Friend (Union Square Press, 2008). What prompted you to write the book? Please tell us a little about it.

I left Vietnam in March 1968 and went on with my life. Twenty-five years later, by chance, I reunited with Kenny Mook, my first best friend in Vietnam. I was a 19-year-old volunteer from Littleton, Colorado, and Kenny was a 21-year-old draftee from Meadville, Pennsylvania.

As U.S. Army infantry foot soldiers, we saw our first bloody combat in Bong Son valley on May 5-6, 1966. Our platoon was trapped and engaged by the enemy at close range. Kenny was severely wounded by a burst of machinegun bullets ripping through his stomach and tearing off half his forearm muscle. I scrambled to his aid and dragged him to safety. He was evacuated from the battlefield and medically discharged from military service.

We reunited on Memorial Day Sunday 1991 at his dairy farm in Saegertown, Pennsylvania. The bullets they took out of his body in 1966 were hanging from a string of leather around his neck. Kenny was my inspiration to write our story and what turned out to be a bunch more stories about my K9 partners; Timber and Clipper in Vietnam.

A Soldier’s Best Friend is written in my own words and in first person. The book covers my two combat tours as an infantryman in South Vietnam (1966-1968). The first few chapters cover my missions with Kenny Mook and the 7th Cavalry. The majority of the book is about my combat missions with the 44th Scout Dog Platoon, handling German Shepherd dogs to hunt and track the enemy in places and spaces only a dog could find.

The story begins with my arrival in South Vietnam as a bewildered 19-year-old recruit. I knew little to nothing about the war, the enemy, or the country of people I was sent there to defend. I tried to put the reader in my boots to understand just how inexperienced I really was; my fears and emotions, death on the battlefield, Timber being wounded, and the exhilaration of saving American lives with Clipper leading the way.

The reader will laugh, get angry, and even shed a tear as each chapter builds on the previous one. Saying goodbye to my scout dogs was a heartbreaking experience. Timber and Clipper were classified as equipment. Timber’s scouting days were over and Clipper continued his mission of saving American lives with another dog handler until he died in Vietnam. I will carry their memories in my heart until it’s time to meet again.

“General David H. Petraeus says the capability they (Military Working Dogs) bring to the fight cannot be replicated by man or machine. By all measures of performance their yield outperforms any asset we have in our inventory. Our Army (and military) would be remiss if we failed to invest more in this incredibly valuable resource.”

“U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Michael L. Oates, in charge of defeating roadside bombs in Iraq and Afghanistan, says the most effective tool is ‘two men and a dog,’ even though the military has spent nearly $10 billion on new detection and clearing technologies.”

Are dogs currently serving overseas in military operations?

Today, the U.S. Army, Navy, Marines, and Air Force deploy military working dog teams throughout the world. The primary dog breeds used are the German Shepherd, Labrador Retriever, and Belgian Malinois. They are highly trained to sniff out explosives, scout and track the enemy, search buildings, and detect narcotics. The U.S. President even has his own military explosive detection dog teams.

A point of interest is that there were no female dog handlers that served in the wars of Vietnam, Korea, or WWII. Today, women dog handlers, trainers, and kennel masters are deployed to war zones in Afghanistan and Iraq just like their male counterpart. Some have served multiple combat tours and some have even been wounded in action. I’ve had the honor of meeting many of them in my travels.

The U.S. military trains and deploys more military working dog teams than any other country in the world. The U.S. also has the largest and most sophisticated dog and handler training complex, and the finest veterinary services and treatment facilities in the world. I’ve recently toured them and they are impressive.

For many years, war dogs were classified as “equipment,” and thus deemed disposable, a heart wrenching reality. Approximately how many military working dogs have served the U.S. since World War I and when did their status change?

The U.S. military did not have a military working dog program until WWII. It was started by the “Dogs for Defense” program in 1942. There were many breeds recruited for jobs such as Scout, Sentry, Messenger, Sled Pulling, Search and Rescue, Mine Detection, and Equipment and Medical Supply Carrier. Many dogs were rejected for reasons such as health, size, agility, durability, temperament, intelligence, and trainability.

The primary breeds used most were the Doberman Pinscher and German Shepherd dogs. Hundreds were deployed and served heroically in the Pacific and European theaters of World War II. After the war ended, the surviving dogs were returned to the U.S. and discharged to their handlers or the families that donated them.

From 1942 to present day the overall number of service dogs has reached well into the thousands. During the Korean War (1951-1953) the German Shepherd was the primary dog used for sentry and scouting. The dogs were classified as military equipment and no longer returned to domestic life. Their fate remained under military control.

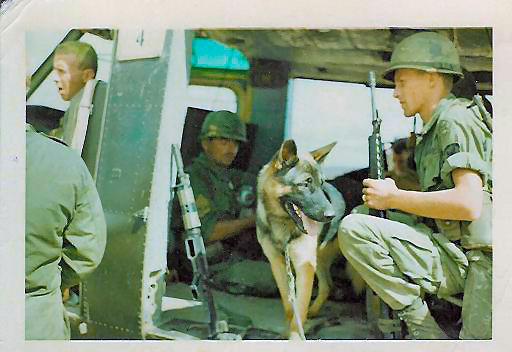

Clipper, scout dog, Vietnam 1967

During the Vietnam War about 4,000 dogs served. By comparison, about 2,600,000 military personnel served within the borders of South Vietnam (1965 – 1973). The success of the dog teams on the battlefield was immeasurable. The primary breeds were the German Shepherd dog and the Labrador Retriever dog. Classified as equipment, most of the survivors were left behind and either given to the South Vietnamese Army or euthanized after the U.S. ground war ended in 1973. A few hundred made it out of Vietnam to serve in other duty stations, but none were returned to an American domestic life.

In the year 2000, Dr. William “Bill” Putney, WWII Marine Corps Officer, Veterinarian, and War Dog Platoon Leader got together with U.S. Congressman Rosco Bartlett of Maryland. Together, they drafted a congressional bill of resolution to authorize American civilians to adopt military working dogs upon their retirement.

President Bill Clinton signed that bill into law on November 6, 2000. To date the U.S. military has discharged hundreds of dogs to loving homes across the America. Dr. Putney passed away in 2003 after his book, Always Faithful, was published.

John Burnam and Clipper, Vietnam 1967

John Burnam and Clipper, Vietnam 1967

Due to your efforts, and those working with you, a “Military Working Dog Teams National Monument” will be constructed in 2011 or 2012. It will be the first time in American history that Congress has elevated an animal to national monument status by law. How did all of this come about?

The congressional legislation for the national monument, sponsored by U.S. Congressman Walter B. Jones, was signed into public law by President Obama on October 29, 2009. Hallelujah! Hallelujah! The law authorizes the John Burnam Monument Foundation (JBMF, Inc.) to build and maintain a National Monument for the U.S. Military Working Dog Teams of all wars. The legislation also states that it must be funded by public donations and grants. The estimated cost is $850,000.

I am the founder of the national monument project and spent years trying to organize and promote a national effort to get it done. I’ve always stated that this monument belongs to the American people, not the government, and that it would take time and effort to get legislation approved by the U.S. Congress. Then it would take a huge public involvement to raise the $850,000 needed to build and maintain it.

I keep in mind that those war dogs NEVER gave up on the battlefield. Retreat was not in their nature and many sacrificed their lives to save American lives. Dogs can’t speak for themselves, so I’m honored to be their voice. And I can’t give up on their national monument just because it’s hard volunteer work, long hours, and takes years to accomplish.

I’ve met with many congressmen and senators on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C., asking for their support. When I met with Congressman Walter Jones, he was eager to sponsor the legislation, so we teamed up to figure out how to get it done. I was honored to be the only Veteran Dog Handler officially invited to give oral testimony before several U.S. Congressional subcommittees in Washington D.C. The subcommittees approved the need for a national monument and moved the legislation into the U.S. House and Senate for a vote, and now its public law.

I remember a reporter once asked me, “Mr. Burnam, what if Congress rejects the legislation?”

I thought about it and then replied, “I would organize the Million Dog March on Washington D.C.” Imagine that scene marching down Constitution Avenue and the headline in the Washington Post.

Scale model of future Military Working Dog Teams National Monument

Where are you in the process of designing and building the monument? How can others help with the project?

JBMF, Inc. has a terrific team of professional volunteers to help get the job done. Our commitment and passion is driven from our hearts for these animals. Our monument design concept has met the standards and engineering requirements of the Department of Defense Military Working Dog officials and other Pentagon executives. This is a huge endorsement.

The next official step in the process is acquiring the land to place the monument at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. Don’t worry! The site will be totally accessible to the public and is only 30-minutes from downtown Washington DC. Dogs are also welcome to visit, by public law, because we placed it in the legislative language of the bill.

Thanks to public donations, we were able to cast the approved miniature silicone bronze statue of the monument’s pedestal figures (four dogs and a dog handler). As we continue to raise public donations, we will build full size components, incrementally, until we have completed the full design. Our goal is to dedicate the monument in 2012 if we can raise the $850,000 by end of 2011.

To help raise funds, JBMF (www.jbmf.us) will be selling miniature 18-inch Bronze, 12-inch Bronze, and 12-inch Resin models of the monument’s pedestal. Hats and t-shirts are already available for sale. Other items will be added as we receive more donations.

Everyone can help! We need volunteers to hold fundraisers in their areas of residence or business. Let your imagination run wild with an idea of how you can raise funds. JBMF will provide supporting materials and even speak at your event, so please contact us. This is a national project and we can’t do it alone!

JBMF, Inc. is a tax exempt charity, so all donations are tax deductible.

John C. Burnam, Vietnam 1967

Has God ever provided an unexpected “detour” in your life that turned out to be positive?

There have been several times throughout my life that I believe God has impacted my decisions that changed the direction of my life for the good. I especially felt God’s spiritual presence in Vietnam, because there is no way I should have survived the horror I experienced on the battlefield. I often wonder why I lived and those next to me did not. I also believe that the heavenly spirits of those young men and dogs give me the strength, energy and focus that direct my passion on the right path to accomplish my mission for them.

Please share one particularly poignant story about Timber and/or Clipper, two of your canine partners in Vietnam.

When I first arrived for duty with the 44th Scout Dog Platoon in March 1967, I was assigned a German Shepherd scout dog named Timber. He was always in a foul mood and aggressive. He’d only calm down after we started working. He was smart and performed very well through the scouting scenarios and obstacle course drills we had set up in base camp. Mission ready training was very important.

The job of a scout dog team is to lead combat infantry patrols into enemy territory and provide an early silent warning of danger. My job was to follow Timber, connected to his leather body harness by a short leather leash. I had to learn to trust Timber’s natural instincts and trained ability to alert me of danger. While following behind at his pace, my job was to keep my eyes on his body language as we slowly navigated through various terrain, jungle, and weather conditions in search of a lethal and well-hidden enemy.

Timber was wounded in an ambush. Although I was okay to continue missions, Timber was never the same. He had had enough of the war and shied away from being handled. I learned first hand that dogs suffered wounds, combat fatigue, and emotional problems just like soldiers. We treated our injured dogs with the utmost of respect and consideration.

I was assigned my second scout dog, Clipper. He and I got along great. Clipper was a lovable dog who enjoyed being around people. Clipper was also extremely bright and easy to command in any situation, as I quickly found out when we were put to the test of combat.

The majority of the dog stories in my book are about my partner Clipper. We scouted together for ten months and I was never wounded again. Clipper saved many lives, including my own by alerting on trip wired booby traps, enemy ambushes, hidden tunnel complexes and caches of buried enemy combat supplies, weapons, and munitions. I loved that dog and we were inseparable.

The enemy had placed a price tag on the scout dog teams and hunted them down with extreme prejudice, because the dog teams were getting too good at finding them.

During one mission Clipper alerted on the enemy and then we got trapped in crossfire between the enemy and American lines in a remote area of thick jungle near the Cambodian border. The shooting and explosions from both sides was so intense that the sounds of the vegetation splintering around us got me so tensed up that I thought we were going to die at any second. I prayed to God for our survival as I lay there with my arm around my dog’s body. I could feel his thumping heartbeat and I’m sure he felt mine too. No doubt Clipper knew if we made any sudden moves, it could be lights out for both of us. Clipper was unbelievably calm throughout that death trap and we survived without a single scratch, and I never fired a single shot.

Not far from where we were trapped, fellow 44th scout dog handler, Edward C. Hughes and his scout dog, Sergeant were killed in action. The date was November 27, 1967, four days after we all celebrated Thanksgiving in base camp.

A film company has optioned your book, which chronicles your experiences in the Vietnam War. What can you tell us about the movie and/or screenplay?

Crooked Door Entertainment screenwriter and author, Marnie Wooding, has written a terrific screenplay titled, “MOE,” which was inspired by my book, A Soldier’s Best Friend. I worked with Marnie throughout the process as the technical advisor.

The following is a statement written by film director, Sturla Gunnarsson about his vision for the film, MOE:

Set in the days of the forgotten war in a distant land, this is a film that explores timeless themes of faith, loyalty and betrayal, pitting one young man against traditions and institutions that he thought defined his very being. At its core though, MOE is a simple “boy and his dog” story. It will be visually lush and poetic, utilizing the Southeast Asian locations to full effect and putting the viewer right inside Simon Delmar’s (main character) experience as he struggles to reconcile his family’s proud military tradition and own ideals with the chaos and disillusionments he encounters in Vietnam.

The first part of the film has the intimacy of a love story as he discovers his own true self and the inner strength through the patience, discipline and sacrifice of helping another being recover from grief. That other being is MOE, a war dog recovering from the loss of his handler. This part of the film will have the quiet simplicity of The Black Stallion, focusing on the behavior, rituals and growing bond between Simon and Moe.

The second part becomes an odyssey; Simon and Moe in a dramatic, dynamic run for freedom across an exotic landscape with danger at every turn and only one another to depend on. This part of the film gets to the very heart of the bond between dog and handler, a love, trust and courage that is only ever truly experienced by soldiers in the crucible of battle. The bond they share transcends all others and becomes part of the very essence of their being, defining and setting the course for the rest of their lives.

The Crooked Door Entertainment producers are currently marketing the film in Hollywood for investment funding. The producers hope to premiere the film at the time the Military Working Dog Teams National Monument is being dedicated.

Personally, I’m very satisfied with the screenplay and the many characters are well thought out. I’d rate the screenplay a PG13 because it is not a blood and guts war story.

Do you have plans to write another book?

First of all, I never envisioned writing any book, especially one about my life in Vietnam. This book has placed me in a public situation that I never anticipated or expected. My story has evolved into several major TV documentaries, a feature film project, many TV and print interviews, over a hundred speaking engagements, and launching a national monument project. This is on top of having a fulltime daytime job that has nothing to do with any of this.

That being said, I’ve gathered plenty of material to write another non-fiction book about the many interesting people, places, and dogs I have met as a result of all this. My next book will just have to wait until after we get this national monument funded and built, and the feature film is released to the theaters. It’s an exciting life.

A few fun questions:

If you could choose anyone, who would you chose to play your part in the movie?

A 21-year-old Tom Hanks would work for me. Although I can’t come up with any comparable young actor’s name, my hope is that the film director selects a popular young star with big screen gravitas that can pull off a 19-year-old lead character who truly loves working with dogs. As the technical consultant for the film, I’m excited to have an opportunity to work directly with all the actors selected to be scout dog handlers. That should be an interesting and entertaining assignment. Can’t wait!

If you could pick the soundtrack theme song for the movie, what would it be?

I’m sorry to say I don’t have one to offer. The movie script really captures the incredible bond developed between young dogs and young dog handlers during a controversial war, and leaving the dogs behind breaks everyone’s heart. I can’t think of a song that would encapsulate that theme. Maybe some of the readers here can help me out.

Do you have a dog companion now? If so, please tell us about him/her.

No, I do not have a dog at this time in my life. My current schedule makes it too difficult with a daytime job, the monument project, movie project, and intermittent travel throughout the year. It just wouldn’t be fair to the dog to be left alone a lot. What is fun about most of my travels is that they are dog related, so I get to meet a lot of dogs, both pets and military working dogs. So, I plan to get another dog after my work is done in a few years. Then I’ll take my dog to visit the national monument and tell him stories about Timber, Clipper, Alex, Princess, Troubles, Shadow, Geisha, Cracker, Ringo, and other hero dogs.

Thanks, John. It’s an honor to have you as a guest at Divine Detour—and a fitting tribute as our nation prepares to remember its veterans, as well as those currently serving, on Veterans Day, November 11, 2010.

~ ~ ~

For more information about the War Dog Monument, visit http://www.jbmf.us/.

To donate to the National War Dog Monument project fund, visit http://www.jbmf.us/Ucan-Donation.asp.

To purchase A Soldier’s Best Friend, logon to one of these online booksellers:

– Barnes & Noble: http://search.barnesandnoble.com/A-Soldiers-Best-Friend/John-C-Burnam/e/9781402754470/?itm=1&USRI=a+soldier%27s+best+friend

Read a recent news feature about John and the National War Dog Monument at http://www.northernvirginiamag.com/entertainment/entertainment-features/2010/05/23/war-dogs-remembered.

German shepherd is a very intelligent dog breed. They are often called as hero dogs. 😉

I loved this post. I just went to see the Vietnam Memorial and would have loved seeing the planned one for the dog teams too. Such an amazing meld of man and dog teams with instinct and love. I’m in awe.

Angie

Thanks for visiting, Angie!

We have had GSDs for 35 years with 4 children. This is a story I would write (if I had been there) in a heartbeat. John, you are sooo blessed to have the opportunity to share. My husband is a Vietnam vet (1st Cav and 9th infantry) and finally taking some action to heal his mental wounds by attempting to bring the Vietnam Wall (5/8’s version) to Arlington, WA in 2011. Now that he’s retired he finally figures out how to really live! I am going to buy this book for Christmas. Our GSD Saphira can look at the pictures :). We will all go to the movie!!

[…] Trei’s Two Cents: Why the Wii Won the War Divine Detour – Kathy Harris » Blog Archive » John C. Burnam: Writing History — … christmas,merry christmas–Christmas turkey dinner for less than £3 a person? | Athletic […]