by Melanie Dobson

An imposing statue stands outside the National Archives in Washington, DC. On the limestone throne of this monument is a sculpted man with a scroll in one hand and a massive book in the other. Etched below his studious pose is this inscription:

Study the Past

But why is it important for us to study the past?

Writers and historians dig through ancient scrolls and books for countless reasons, but as I searched for the answer to this question, I discovered three reasons why we should all be students of history. Why we should all read the stories of those who’ve gone before us.

Identifying Trends

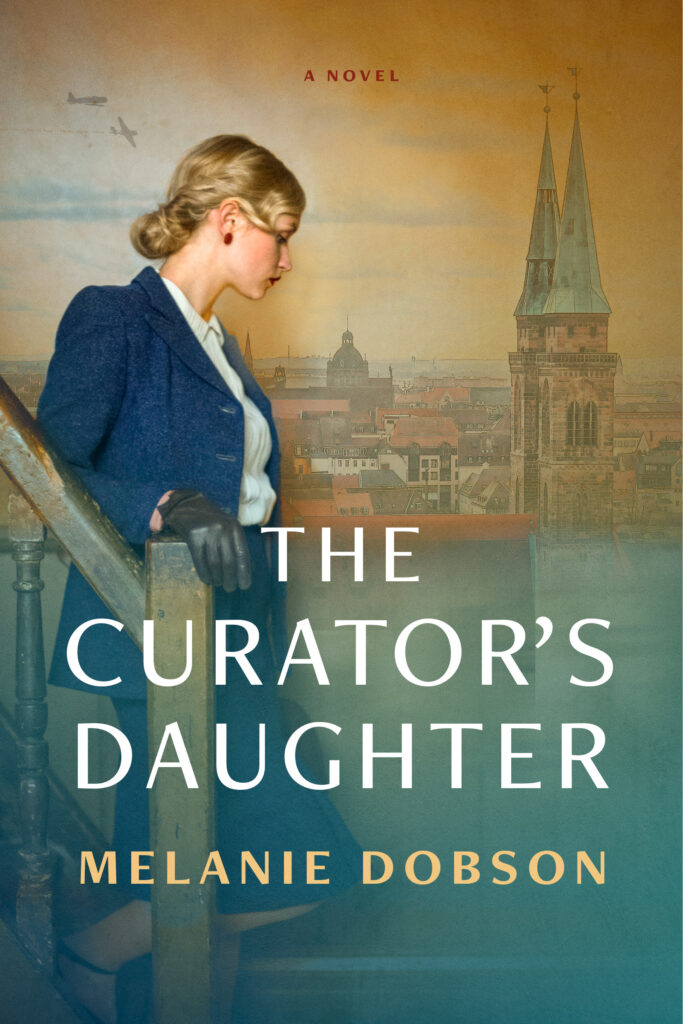

Racism, the suppression of free speech, rioting, a pandemic—four of the primary issues our country is facing right now are the same threats that the historical and contemporary characters confront in my new time-slip novel The Curator’s Daughter. While I wrote this work of fiction in 2019, I had no crystal ball to see into the future. The stage, sadly, was already set for a crisis.

Identifying trends is one of the main reasons why we should all study history. The Curator’s Daughter is mainly a story about the Holocaust, but it circles back almost seven hundred years to the Black Death, which ignited a violent anti-Semitic blaze across Europe. The Jews, their enemies said, caused the plague by poisoning wells. As a result, more than two hundred Jewish communities were destroyed.

Hundreds of years after Jews were murdered because of the plague, another blaze of hateful rhetoric and lies hit Europe. Adolf Hitler convinced millions of Germans that the Jewish people instigated their humiliating loss of the Great War. His hateful words soon turned into action, and a different kind of plague killed more than six million Jews and countless others from around the world.

At times, this hatred feels like a never-ending cycle as the spokes of another year, decade, century circle around. And free speech, one of our nation’s most valuable commodities, is being threatened as well.

Instead of studying the past today, identifying trends through the years, our society often edits history. In the name of respect, we try to erase the most shameful events. Cover up the embarrassing pieces of our history when we should be shining light on the most horrific of times, sifting through these events to find out what went wrong.

Chronological snobbery is what C. S. Lewis called a civilization that believes it is above repeating the catastrophic events of the past. But instead of believing ourselves to be better than those who came before us, we should humbly admit that we are susceptible to a repeat. As a society, we must identify what went wrong in the past to stop the cycle today. A hard brake before we crash again.

Defeat Evil

We must study the past so we don’t repeat the genocide from hatred, the animosity that destroys people and communities alike. Then we utilize this information so these same evils don’t cycle again on our watch.

Each individual has a different role in stopping the destruction, a different weapon to wield in fighting evil. When we see the attack coming from afar, how do we gird up for a battle? What weapon do we have to fight?

For our first responders and military, it might be a literal weapon, but for most of us, we fight with our words. Some of us battle by stepping into the political arena or writing down our stories or teaching our children lessons from the past so they can fight evil alongside us. Others stop the onslaught of evil with love and forgiveness as they care for those who have been wounded in the midst.

Tosha Lamdin Williams, the founder of Family Disciple Me, recently wrote an article called “The Tale of Two Harriets” about two heroic women in history—Harriet Tubman and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Both women balked at the cultural norm of slavery in the mid-1800s and fought in their own way to free slaves. Harriet Beecher Stowe battled the evil of slavery with written words while Harriet Tubman escorted slaves to freedom. Instead of running away, hiding from evil, these Harriets fought with the weapons of grace and truth.

We read history so we can learn the stories like these and the strategies of how others defeated the evil around them. Then we get to work right where we live, searching for ways to redeem the ruins in our world.

Finding Hope

Finally, we study the past in hopes of replicating good choices and replacing bad decisions with better ones. We study it to find hope after a cycle of hatred, peace after a pandemic, reconciliation after a family rift. In the pages of history, we find victory that we can cling to as we seek restoration.

We are inspired by the stories throughout history of ordinary people like the two Harriets who did extraordinary things to care for their neighbor. By those men and women courageous enough, even when they were afraid, to stand for what was right.

On the other side of the National Archives door is a second statue, this one of a robed woman engrossed in another book. The words under her sandaled feet read:

What is Past is Prologue

Both statues in front of the National Archives doors were carved in the 1930s—a prologue for us living in 2021—but the reminders on these towering monuments are just as relevant today as we write a new prologue.

Our society is at a crossroads again. Will we wield our words with grace and truth today, or will we be defeated by the evil around us? As we circle again this labyrinth of time, it’s critical that we step mentally into the past and study it. Search for ways to defeat evil and find doors of hope for the next generation.

Melanie Dobson is the award-winning author of more than twenty historical romance, suspense, and time-slip novels, including The Curator’s Daughter, which releases from Tyndale House Publishers this month. Melanie is the former corporate publicity manager at Focus on the Family and owner of the publicity firm Dobson Media Group. When she isn’t writing, Melanie enjoys teaching both writing and public relations classes. Melanie and her husband, Jon, have two daughters and live near Portland, Oregon.